Other Terms and/or Related Concepts

Mantra argument; using emotive language; appealing to sentiment; cliché thinking; reflex thinking; mindless repetition.

Description

Argument by slogan and the family of fallacies associated with argument by slogan (see other terms above) all have in common an intent on the part of the advocate to sidestep the issue under discussion and to "wrong-foot" the opponent. Instead of logically advancing a viewpoint and dealing with any challenges to that viewpoint, the advocate seeks to wear opposition down by repeatedly asserting a simplistic view of the issue.Example

At a rally to protest a meeting of the World Economic Forum, Brenda Dudgeon is challenged by a forum delegate from the Seychelles, who asserts that his country needs foreign investment to progress. She picks up her megaphone and begins to chant: "Global capital oppresses the poor! Global capital...". In due course, other protesters take up the chant and the delegate from the Seychelles is drowned out.Comment

There may or may not be some validity in the assertion that "global capital oppresses the poor". Whatever the truth of the matter, the issue is far more complex than the slogan; and use of the slogan will not advance understanding. If Brenda's behaviour is extremely confrontational, she may even appear on television coverage of the event. If this is her sole aim, she has been successful. But her behaviour is most unlikely to persuade the uncommitted to her view and it is very likely to entrench opposition to her view. Arguably (and ironically), the group least likely to benefit from her sloganeering is "the poor".If Brenda's beliefs are sincere, and if she wishes to address the causes of poverty in the third world, she needs to engage in productive debate after some thorough self-education on the issues. She needs to break out of her coterie of like-minded activists and to substitute sober reflection and hard work for the "warm inner glow" of sloganeering. If after sober reflection, Brenda has concluded that the unfettered flow of capital around the world is a primary cause of poverty, she will be able to mount a convincing argument. In advancing the argument, she will have supporting evidence for her views and practical suggestions for capital regulation. The uncommitted will seriously consider her perspective. In due course, and in her own small way, she might even advance the plight of the world's poor. It won't be as much fun as public posturing, chanting and sloganeering, but she might actually get results.

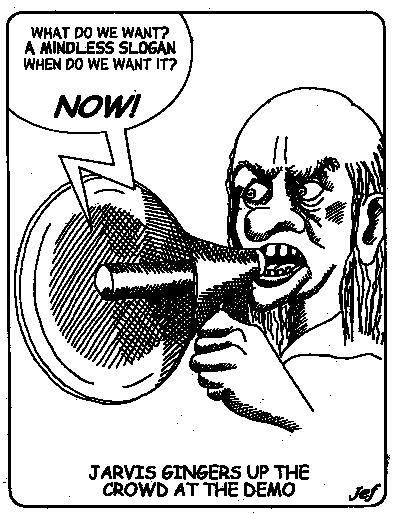

The sight of a large group of self-satisfied demonstrators marching under a banner and chanting: "What do we want?" is now a commonplace. This ritual public performance may be boring, alarming, amusing or inspirational to the onlooker - depending on his or her political beliefs, and on what answer the demonstrators give to their rhetorical question ("what do we want?"). To the critical thinker, participation in a mindless crowd of sloganeers is not an effective vehicle for productive engagement with a substantive and difficult issue. It can raise awareness or show there is popular support for the cause being protested. However, often a march under banners, accompanied by an orchestrated chant is more about socialising and group cohesion - rather than a serious attempt to right a wrong, or to initiate political or social change. In most such "demos", visceral posturing has triumphed over intellectual engagement.

It is possible for argument by slogan to manifest itself in even more mindless ways. One of the most outstandingly mindless is the mass-produced "bumper sticker". Sloganeering marches may be futile, but at least walking and chanting is a mild form of healthy exercise. Political bumper stickers really only have one message, whatever the actual words on the sticker itself. The message? "I am a clueless poseur and I apparently believe, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that an infantile declarative statement stuck on the outside of my car amounts to a persuasive argument. Further, I am so bereft of wit, imagination, initiative and literary skills that I have to purchase the sticker off the shelf, rather than creating one of my own."

We know that this might seem to some to be a harsh judgment. But truth must prevail, even if the truth offends those asinine advocates who are also sticklers for stickers.