It's been a while since I last wrote a blog post, but with all the recent media attention (and my own interest), I thought it would be interesting to share some of my results in using ChatGPT. Specifically, using it to replicate the things that this blog, a book and podcast did regularly, back when blogs were big and podcasts were small.

What is ChatGPT and how could it assist in teaching critical thinking and analysing arguments?

Unless you've been a participant in the series 'Alone' since December last year, you've probably heard about ChatGPT, the cutting-edge language model developed by OpenAI that utilises deep learning techniques to generate human-like text. The recently media attention has highlighted its potential to revolutionise various industries and applications, including education. While there are plenty of potential challenges of AI in education, an interesting application of this technology is its potential to help teach critical thinking, informal logical fallacies, and how to analysise/improve arguments.

ChatGPT can be used to generate realistic examples of common logical fallacies and explain where the argument goes wrong. This can help students develop the skills necessary to recognize and avoid these fallacies in their own arguments and in the arguments of others. For example, it can generate a statement like "Vaccines cause autism" which is (sadly) a common logical fallacy called False Cause.

Additionally, ChatGPT can be used to analyse and evaluate arguments by generating counterarguments and identifying any weak points in the reasoning. For example, it can be used to evaluate an argument in favor of increasing the minimum wage, by generating counterarguments such as "increase in minimum wage would lead to inflation" or "small businesses would suffer" and help students identify any weak points in the reasoning.

You can also use ChatGPT to facilitate discussions and debates by generating thought-provoking questions and prompts. For example, it can generate a question like "Should the government regulate social media to combat misinformation?" this can help students to consider different perspectives and to develop their own critical thinking skills.

Overall, ChatGPT has the potential to be a valuable tool for teaching critical thinking, informal logical fallacies and to analyse people's arguments. Despite concerns about the potential challenges of AI in education, the technology holds a lot of potential in various fields. As the technology continues to improve, it will likely become an even more powerful tool for educators and students alike.

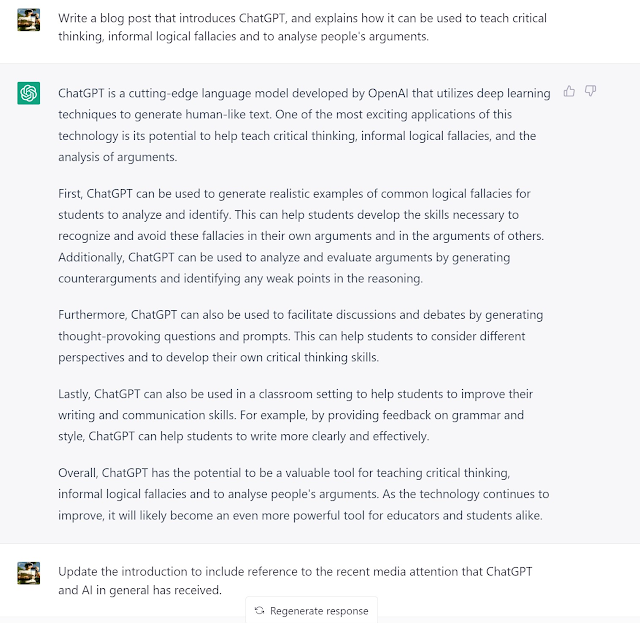

Hopefully anyone who has played around with ChatGPT has reaslised by now that most the above is a copy and paste from ChatGPT. It's too well written to be me (and it's kind of boring and lacks my use of irony or references to TV shows).

See below for my initial few prompts and its response.

Using ChatGPT to generate an explanation for concept, such as an informal logical fallacy.

Using ChatGPT to analyse an argument.

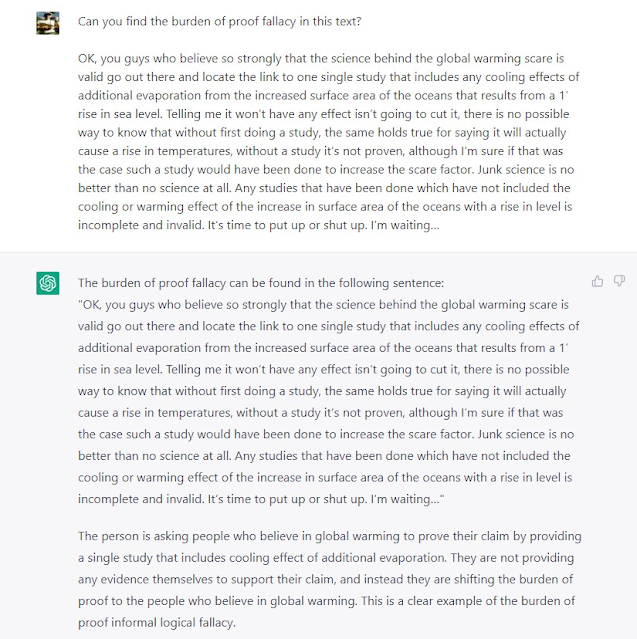

I then decided to see how it would go assisting me in analysing text for fallacies, which is pretty much the entirety of this blog. So I tested ChatGPT against some text from this post: No conflict here, just scientists doing their jobs - you know - science.

Okay, I told it to look for a particular fallacy. So how about just looking for them in general?...is more a tool to consult as the occasion demands, rather than a book to read in a linear fashion. You may find it to be a useful resource for those occasions when you read or hear a suspect statement or claim, and want to identify the flawed reasoning in the assertion.